Pragmatism and Zen

Written by: Nyogen Senzaki

Translated by: Nathaniel Gallant

Published in: Essays Volume 1

Written by: Nyogen Senzaki

Translated by: Nathaniel Gallant

Published in: Essays Volume 1

Whenever Schopenhauer lectured, instead of addressing the audience as “ladies and gentlemen,” he would begin by calling out to his “Mitledeinde!”—his allies in suffering. Buddhists as well see the world as a place of pain and difficulty, and so people from Shakyamuni to the collected ancestral teachers, especially those who pioneered the way of Zen, have used the word bosatsu to address friends of the Way in this world.

Bodhisattva in Sanskrit and Bodhisatta in Pali, when transliterated in Chinese phonetics, took only the first and third syllables to become bosatsu.1 Bosatsu have appeared as statues and so on made from gold-leafed wood, stone, and ceramic, like Jizō Bosatsu and Kannon Bosatsu, which has made people think that bosatsu exist apart from our present lives. However these are the “blockhead bosatsu,” and do not deserve to sit alongside those who practice Zen.

Bodhi refers to the Great Way. It is truth. Satva or Satta refers to sentience, meaning any person who has the potential to practice. A bosatsu is therefore someone who walks the Great Way. They are someone who has had a direct experience of and realized truth. As such, anyone in our present world who is awakened is a bosatsu. There are blue-eyed bosatsu, brown-eyed bosatsu, bosatsu who invent things, reporter bosatsu, soldier bosatsu, politician bosatsu, film actor bosatsu, bookkeeper bosatsu, typist bosatsu, farmer bosatsu, industry bosatsu, mother bosatsu, wife bosatsu—the list is endless. In other words, according to Mahayana Buddhism, anyone who has deeply studied the nature of life and has come to have a proper perspective on it, and as a result has a desire to contribute to the welfare of the world through their work, is considered a bodhisattva. In this way, there are also many exemplary bosatsu among Christians; whereas most Buddhist monks are in fact failed bosatsu.

Life in America, in both war and peace, can seem to move at a dizzying, frantic pace. Everyone is caught up in a whirlwind effort to build and make things. However, on what kind of ideal is all of this based? Many have wrongly claimed that it is worship of the “almighty dollar,” but America’s national credo is more than simple materialism. Rather, it is pragmatism that has served to set a tone for their philosophy of success and the teachings of energism,2 which show us the true American way and the humanism at its foundation, singular among the contemporary world of ideas. This pragmatism is centered in humanity, attempting to view all things in heaven and earth just as they are, within the domain of man. Having been built around humanity, one of pragmatism’s defining qualities is a lack of reverence for the divine or the mysterious beyond man. This without question resonates with Mahayana Buddhism, and in particular Zen Buddhism. In the Brahma’s Net Sutra, Sakyamuni says that “You all will become Buddhas and I have always been a Buddha. “Those who honor the teachings of Shakyamuni are all future Buddhas, that is, bosatsu. Shakyamuni attained his great awakening through the power of meditation and became a Buddha as an example for us. Upon doing so, he said that all living beings “possess the wisdom and virtue of nyorai,”3 which is proof that there is potential for us to become Buddhas in the future. However, the “future” does not mean the next life. We are fit to become Buddhas in this mind and body, through what we say and hear now, just as we are. We do not go to a Heaven or Pure Land apart from this world to become Buddhas. We become Buddhas in this world with its moon, flowers, and edifices. This life, in which we fight for justice and pursue our passions, stirred by our affections and welling up in pride—this is the life of the Buddha, just as it is. Anyone who thinks reading scripture or visiting temples smells of false piety would do well to study the famed American philosophy of pragmatism, and from there enter into Zen. They will soon gain a grasp of Zen and be able to understand scripture clearly, and the true significance of visiting a temple. America should not be looked down on for the spurious notion that it is a land where wealth is worshipped.

The whole of Europe once derided the intellectual world of America. They have said that even near the end of the 19th century, American philosophy was a shadow of the thought of other nations, and that it had no philosophy of its own. It was around that time, however, that a very particular philosophy began to bud in America. Still in its nascence throughout the first part of the 20th century, it has at last broken through its bud and flowered. The flower of this philosophy is pragmatism. Although pragmatism has been criticized as a form of realism and utilitarianism, the basis of this philosophy has come to form the psychological foundation of the American people. Even for those who would never call it a philosophy, it is through these ideas that they view life and define their own place in the world.

This philosophy of realism is the gospel of energism and has created a heaven in this world called “success.” American business can thank this philosophy for the might of its forward momentum. As Americans continue to persevere and invent, it is this philosophy leading the way behind the scenes of all their progress and innovation.

1 When Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese from various South Asian languages, many terms such as this were transliterated. Bodhisattva became 菩薩, pusa in its Chinese reading and then bosatsu when transmitted to Japan.

2 A set of philosophical principles popular in the late 19th century that consistent and vigorous activity was the key to human life and success.

3 Nyorai (如来) is the translation for tathagata, meaning one who has “thus come,” or attained enlightenment. It is also used as an honorific term for Buddhas in East Asia.

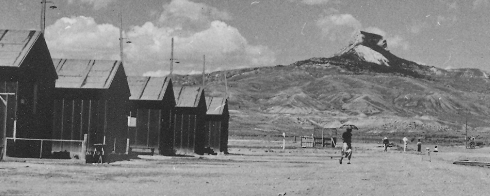

What is the Heart Mountain Bungei? Learn about the story behind the poetry and prose of the collection, and the process of translating and interpreting the Bungei.