Living for Hobbies

Written by: Tanahashi Sōji

Translated by: Joseph Boxman

Published in: Short Story Volume 1

Written by: Tanahashi Sōji

Translated by: Joseph Boxman

Published in: Short Story Volume 1

They say people live for their hobbies. I have found this to be true in my experience, and I believe it is also true that there is no person alive today who does not have some type of hobby or special interest. People take up all kinds of hobbies, but generally speaking, men tend to favor hobbies that make money, and ladies tend to show more interest in things like fashion.

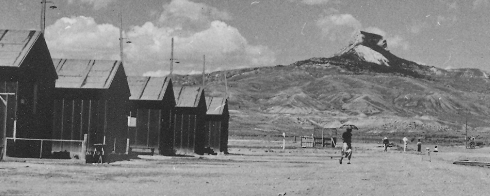

Being forced to live our lives under such strange restrictions within the confines of this camp has resulted in our hobbies taking a turn toward the bizarre.

Over the summer, a neighbor of mine named Kurō had taken up the rather shocking practice of catching rattlesnakes and keeping them as pets. Day after day he would go out and scour the wilderness around the camp for them, coming back to report with glee how many he had caught each day. He loved the terrifying sound of their rattles so much that he kept them in a wire cage just to listen to them. This pastime kept him occupied for some time, but then all of a sudden one day there was an order from the camp office banning such practices, claiming that the snakes were too dangerous. I do not know what he did with them, but in short order all the rattlesnakes were gone from the cage.

A few days later, the same cage that had held the rattlesnakes now held a small animal of a type I had never seen before. I learned later that it was called a chipmunk.1 It was far cuter than any rattlesnake. It would sit up and use its front paws for little hands like a monkey, and if you gave it a nut, you could watch it open it up and eat it with those nimble paws. Once in a while it would even show us how it could run on a little wheel like a pet mouse.

One day I found Kurō laying a good amount of cantaloupe seeds out to dry in the sun. Aha! I thought to myself: he’s going to feed these seeds to his chipmunk. He pampered his pet and would collect different nuts from here and there that he thought it might like. As long as it stayed in its cage, it wanted for nothing and could continue to live its life in safety and ease, without fear of being attacked by outside predators. I felt that there was something about its situation that is remarkably similar to the one we are in now. This must be what we look like from outside the barbed wire fence: like we are living easy with all our basic necessities provided for by the government! I thought about how much better off even the poorer families among us would be if they were able to work outside of the camp to make ends meet. Even if the small rodent would do nothing more interesting in the wild than look for nuts when hungry and sleep in its burrow when tired, I could not help but think it would be much happier out there, outside the cage.

1 The author’s nonstandard katakana spelling of this word (チープモンキー) suggests he has misheard it as “cheap monkey,” perhaps an ironic reference to the treatment of people in the camp.

What is the Heart Mountain Bungei? Learn about the story behind the poetry and prose of the collection, and the process of translating and interpreting the Bungei.